Museum as artifact

TheStar.com - News - Museum as artifact

Libeskind's work may be about spectacle, but the Crystal is neither flashy nor crass

May 26, 2007

Christopher Hume

In the case of the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, which opens next Saturday at the Royal Ontario Museum, what you see is not what you get.

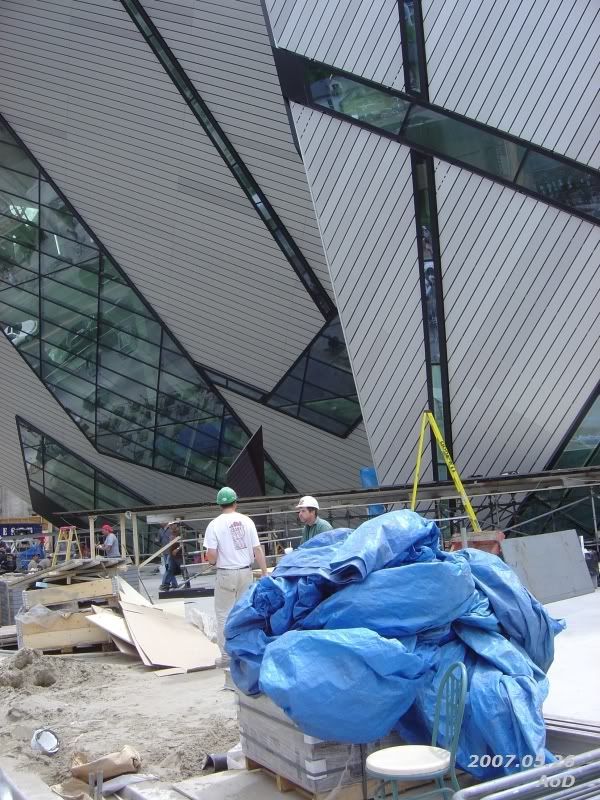

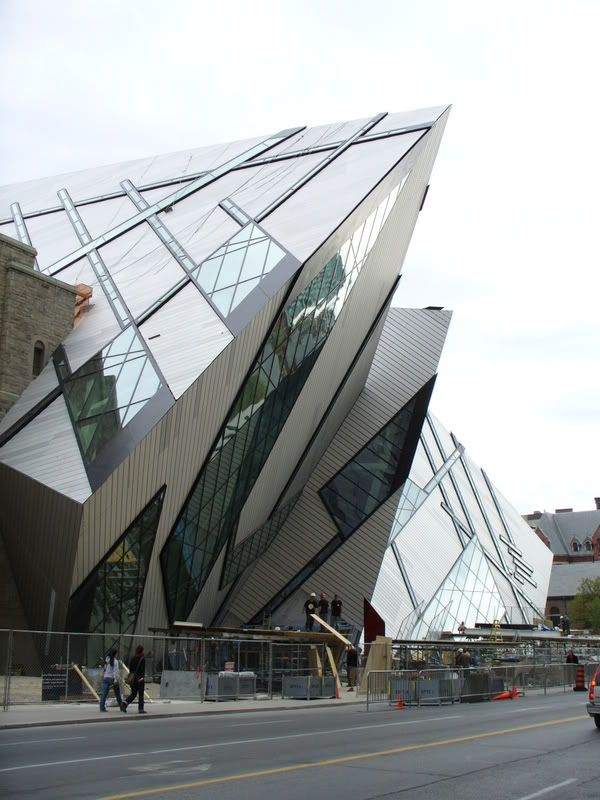

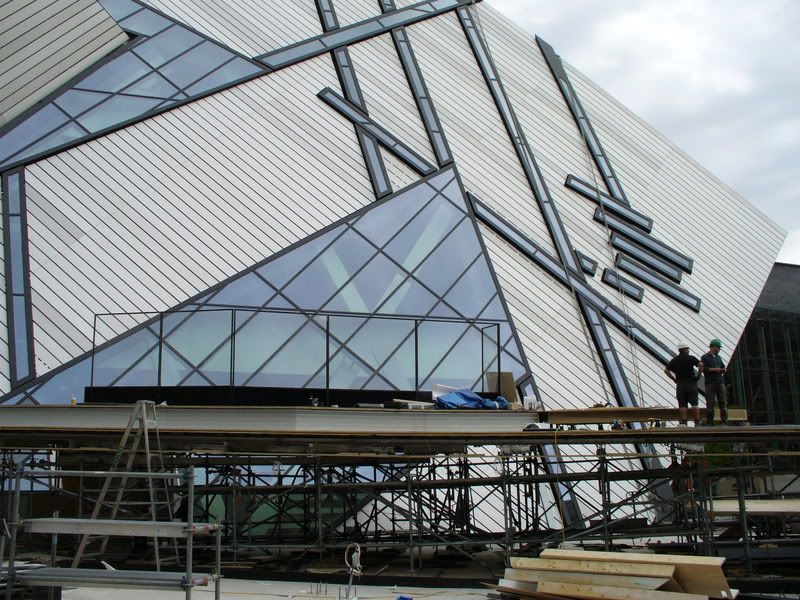

From the street, the $270 million addition is sharp-edged, hard-surfaced, angular and aggressive. Step inside, however, and it suddenly becomes gentle, meditative, all about creating connections and a sense of intimacy.

Designed by New York-based Daniel Libeskind, this is 21st century architecture at its most brilliant. Make no mistake about it; this is Libeskind at his best. True, the Crystal bears an uncomfortable resemblance to many of his other projects – the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the Denver Art Gallery, for example – but to put it simply: it works.

Though he can be rightly criticized for approaching architecture as an exercise in applied style, the Crystal shows Libeskind's remarkable ability to create beautiful spaces, if not exquisite objects.

And despite its deliberate in-your-face esthetic, here's a structure that spares no effort to give back to the city as much as it takes, no, more. Now that the ROM's entrance is on Bloor St., set back as much as 20 metres from the sidewalk, we will soon have a new public space on one of Toronto's most important intersections. It's this kind of commitment to urbanity that raises the Crystal to the level of greatness.

Libeskind has also managed to bring a sense of urbanity to the interior of the Crystal, which reads like a series of spaces joined by walkways, bridges, vantage points and windows. Clearly, the building was designed to provide maximum pleasure to visitors, to be an artifact in its own right, not simply a receptacle, the "black box" that obsessed curators for far too long.

In this manner, though it in no way looks like the ROM's two original wings, it shares with them a desire to delight and engage its audience. Walking through the new spaces, visitors will be struck by all the gestures, large and small, that have been added for them to enjoy. The walls that have been peeled back to reveal details of the original structure; the views between floors and galleries; and the marvellously respectful relationship between old and new.

No one is better than Libeskind at transforming utilitarian elements into architectural features in their own right.

The Stair of Wonders, for instance, is the central vertical spine that extends from the basement to the fourth of five floors, filled with more than 1,000 objects, unusual and unique items from the ROM collections including seashells, antlers, toy soldiers, insects and miniatures. This isn't the kind of space that one enters and leaves the museum behind, but rather part of the main event, practically a gallery in itself.

Most people will access the stairwell from the main entrance on Bloor. It's part of a vast new atrium that also contains the ROM's shop, ticket counters and a strange, very Libeskindian room called the Spirit House. Its multi-planed walls are interior extensions of the five "crystals" that form the exterior. These walls run almost to the top of the addition, the space they define visible from almost every level.

Much like the Void, a slice of emptiness bisecting the Jewish Museum that recalls the rupture of the Holocaust, Spirit House will be not be programmed. Filled with nothing but chairs, it is a room for contemplation and reflection, if not quietude, a reminder that the new museum is not a glorified daycare centre, something that previous ROM director and CEO Lindsay Sharp seemed desperate to bring about.

From the start, the current leadership, headed by William Thorsell, has been determined to restore the ROM to the adult world, to halt the dumbing-down of the institution, an attitude that flies refreshingly in the face of the 21st century.

Indeed, as much as the new ROM may be about spectacle, especially architectural spectacle, there's nothing flashy or crass about it. Above all, one can't help but admire the thoughtfulness that has gone into arranging these new spaces. The second floor, for example, where the dinosaurs will be displayed, is large, well-lit and nicely connected to the city beyond. With its extra-height ceiling, it has been designed to accommodate the huge fossilized skeletons that will be installed.

Some of these dinosaurs will be visible from the street. Yes, that's right. Despite all the chatter about the Crystal's lack of transparency, this isn't quite true. There are windows, some enormous, that overlook Bloor. The impact is striking; inside, some reach from floor to ceiling to provide a whole new Toronto vista.

The third floor will contain galleries dedicated to Africa, the Americas and Asia Pacific. The ceiling here is lower, which means the spaces are more intimate, in keeping with the nature of the material on display.

Above that, on the fourth floor, are textiles and costumes and the new location of the Institute of Contemporary Culture, previously housed in the basement.

Speaking of the basement, much of it will be given over to Weston Hall, the museum's main temporary exhibition space. Don't forget that once the expanded ROM reopens, costs will increase. At a time of ever-decreasing government funding, that means the pressure will be on to attract more and more visitors.

Temporary exhibitions – read, blockbusters – will be the obvious answer. Though there are never enough to go around, this is where they will be installed, in a space large enough to house even the biggest.

Given that the architect is Daniel Libeskind, no one should visit the ROM anticipating the conventional geometry of right angles and modular grids. This building is all about walls that lean precariously and join together sharply. His is an architecture of the unexpected, even provocative. The square floorplates, rectangular masses and patterned regularity that have typified building typology for millennia have given way to something more random, arbitrary and exciting.

Libeskind compensates for this by setting up connections, visual and physical, at every opportunity. The intention isn't to confuse, but to engage.

The decision to open the Crystal before the exhibits are installed is a smart one; it means Torontonians will have a chance to experience the building purely as a piece of architecture. A similar strategy was used at the Jewish Museum when it opened in 2001 and, according to many, it was more powerful empty than full.

Few of Libeskind's contemporaries have his grasp of the narrative potential of architecture; his buildings manage to tell stories, not just contain them. Perhaps that's why he's so much better doing cultural projects like the ROM than commercial ones such as the ill-conceived and rather awful L Tower, a condo planned for the top of the Hummingbird Centre.

Though it won't thrill everyone, the advent of the Crystal will be good for Toronto. If nothing else it reminds us that growth involves risk. It isn't just the institution that has taken a chance here, it's the whole city.