Beyond Density

Because great cities have short blocks and lively sidewalks, Mississauga wants a downtown grid that lures pedestrians – and Amacon's Parkside Village will help launch the vision

Jan 26, 2008 04:30 AM

Dan O'Reilly

Special to the Star

Mississauga: Long blocks and virtually empty sidewalks.

For now, the vacant 12-hectare site just west of Mississauga's Civic Centre looks like most other potential development sites in suburbia – even if it is part of a downtown.

This spring, however, construction of Phase 1 of Mississauga's first "urban village" will begin, heralding a new era in the city centre's evolution.

In recent years, downtown Mississauga has amassed both significant density and a reasonably broad mix of land uses. But its sidewalks remain virtually empty, especially when compared with the attractive central areas of the world's great cities. And it's that lack of street life that Canada's sixth-largest city hopes to address starting with Parkside Village by Vancouver-based developer Amacon.

Just 30 years ago, the newly constructed Square One shopping complex and some vacant farmland was about all there was in this area. Now, this approximately 160-hectare, special-growth district in the Highway 403-Highway 10-Burnhamthorpe Rd. area really is the heart of Mississauga, says Ed Sajecki, the city's planning and building department commissioner.

A place that once provided little more than shopping and parking now has a fairly broad mix of uses. Besides the Civic Centre, the Living Arts Centre, the central library and other facilities, it's now a prime office and residential area, with new retail and restaurants integrated into the taller buildings.

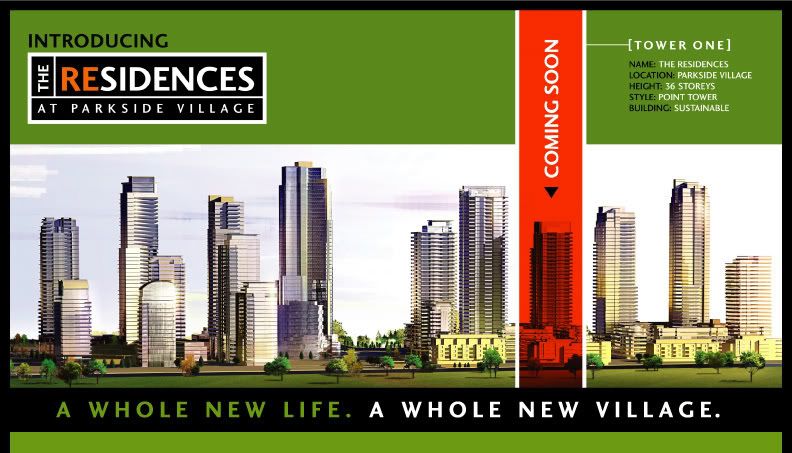

Parkside Village will add a lot more density and broaden the mix of uses. There will be about 5,300 highrise, midrise and townhouse units for about 12,000 people in an 11-block development west of Confederation Parkway, north of Burnhamthorpe. Amacon will also add restaurants, stores, banks, offices and a hotel to the mix, Sajecki says. What makes this development different is the attention being paid to the street grid as part of an effort to enhance street life in an area still dominated by the car.

On one floor at the Civic Centre, there's a large Lego-style model that provides an overview of what the city centre will likely look like in 20 or 25 years. It allows the planning department to add miniature towers as it receives development applications, Sajecki says.

But the less noticeable things at street level may be at least as important to Mississauga's future. They include the planned construction of a new downtown park later this year, the redevelopment of two existing squares sometime in 2009, plus ongoing research into what other cities have accomplished.

Sajecki likes to say the "great cities have good bones," and he has put on presentations that include slides showing how central Mississauga's loose grid differs dramatically from the tight webs of streets common to cities where people like to walk.

"We're looking at what New York, Rome, Barcelona, Toronto, even Portland Ore., are doing," he says. "Our blocks are too long; we know that."

About 2 1/2 years ago, the commissioner and some of his staff travelled to Vancouver to meet with that city's planning department. "Vancouver has a very high standard of urban design," Sajecki says.

Based partly on Vancouver's experience, Mississauga last year created an urban design review panel, made up of architects, landscape architects and planning professionals, to serve as an advisory committee to the city.

As part of the overall review process of the Parkside Village proposal, the Vancouver trip also provided the opportunity to examine the type of projects Amacon and other West Coast developers were doing.

Not only will Parkside Village be one of the largest developments in Mississauga by a single landowner, it will also be one of the densest. But while the scale is large, the amount of detailed planning into the pedestrian-oriented development will set the standards for future development proposals in the city centre, Sajecki says.

Under the "unlimited height and unlimited density" provisions of a secondary plan designed to stimulate the growth of the city centre in the 1990s, Amacon could have pushed ahead with a traditional development. But it chose not to go that route, says Marilyn Ball, the city's design and development director.

"They cut the blocks in half," she says, citing Amacon's decision to divide the development into manageable blocks, which will result in a more urban-style, compact street grid.

There will be nine development blocks and two designated park blocks, which will help form a corridor of green space linking the Mississauga Civic Centre with Zonta Meadows, a city park to the west of the development, she says.

The development blocks will be dotted with "point towers" of varying heights, which will serve as a buffer and transition area for a single-family subdivision, also to the west. Point towers are tall, slender buildings set back from the street on podiums, instead of the more traditional massive condominiums built at grade, Ball says.

"They're more pedestrian-friendly. As you walk by them on the street level, you're not as conscious of the tower."

Another hallmark of Parkside Village will be a "sophisticated mix of uses," including ground-floor retail shops, especially along Confederation Parkway, she says. Other examples of the intensive detailed planning include maintaining a 30-metre space between adjacent residential and commercial towers and the avoidance of blank walls or other "dead spots" at grade.

"The city didn't want areas where there is no life," explains Sal Vitiello, principal, E.I. Richmond Architects Ltd., the Toronto-based architects for the developer.

Amacon has already established a strong presence in the city centre area with two fully occupied condo buildings, a third under construction and a fourth in the planning stages. But the inspiration for Parkside Village are the projects that Amacon and other West Coast firms have undertaken in Vancouver, Vitiello says.

"There is definitely a unique and recognizable approach to planning and urban design principles in Vancouver, and many of these West Coast approaches have been incorporated into the design. These include an emphasis on curb appeal, encouraging an active street life, the use of point-tower architecture and a focus on buildings at grade."

Almost five years of planning and negotiations with the city have been invested in the project. It was a process that encompassed countless meetings with city staff, recreating an original design and the hiring of Urban Strategies, a Toronto planning firm, to create the detailed design components. The result was an urban design document that serves as a guide for the planning principles.

Not only is Amacon the first developer in Mississauga to produce such a document, it's also the first to have its plans reviewed by the city's the new urban design review panel. The document will be incorporated into the development agreement, Vitiello says.

With its planned at-grade retail space on Confederation Parkway and partly along the internal side streets, Parkside Village won't be the type of condo development where residents simply come home at night and don't venture outside again until the following morning, says Lilliana Di Franco, Amacon's marketing and sales vice-president. "It will be true urban village with activity," says Di Franco, who helped create the original concept vision with Amacon president Marcello DeCotiis.

Sidewalks will be between 10 and 12 feet wide but at the corner of Princess Royal Dr. and Confederation Parkway, "the sidewalk will be approximately 30 feet in width to create a focal point and allow for café seating and an active street life and gathering point," she says.

Phase 1, with one 40-storey and two 36-storey condo towers, is scheduled to begin this spring.