Pep'rJack

Active Member

.

Two Infusions of Vision to Bolster New Orleans

by NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

August 28, 2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/28/arts/design/28jazz.html

In the two years since Hurricane Katrina, what has the rebuilding effort produced? No grand designs. No inspired vision for the future of New Orleans. There have been only a handful of earnest, grass-roots proposals to preserve what’s left of the historic fabric.

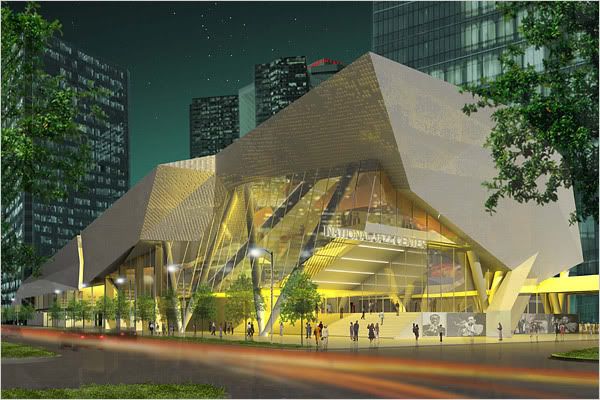

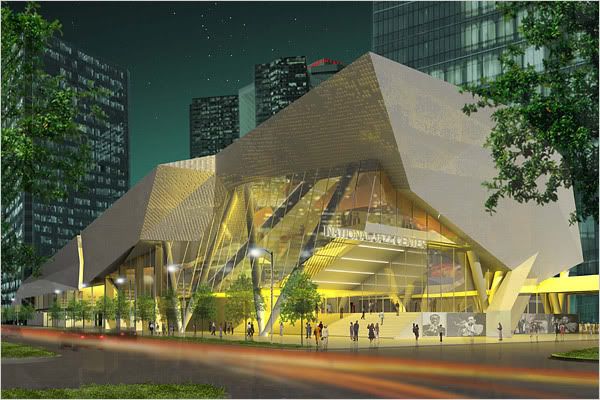

Amid this atmosphere of malaise, two recently announced projects for downtown New Orleans stand out as the first truly creative attempts to foster the city’s resurrection. The first, an extravagant proposal for a new New Orleans National Jazz Center and park by Morphosis, is the most significant work of architecture proposed in the city since the Superdome. The second, a six-mile-long park and mixed-use development along the Mississippi, designed by TEN Arquitectos, Hargreaves Associates and Chan Krieger Sieniewicz, would undo decades of misguided building on the riverfront.

The design of the riverfront project has yet to be finished; even the developer concedes that it would take years to build under the best conditions. And construction of the park would probably require the cooperation of city, state and federal agencies — an almost laughable notion, based on recent experience.

Still, the scope and creative ambition of these projects suggest how architecture could someday be vital to the city’s physical and social healing. Both seek to transform dead urban areas into lively public forums, employing powerful architectural expressions of a democratic ideal.

The proposed Jazz Center, designed by Thom Mayne of Morphosis in Santa Monica, Calif., is conceived as a great social mixing chamber, with music embedded in its core. For architects, its form may bring to mind early-1960s “Walking Cities†fantasies by the British firm Archigram: gigantic nomadic machines that could carry entire urban settlements in their bellies.

The center, however, is firmly rooted in the postwar context of downtown New Orleans. Situated on the corner of Poydras Street and Loyola Avenue, it would be flanked by cool glass towers. An elevated section of Interstate 10 cuts through the city just to the west; the imposing form of the Superdome, its broad crisscrossing ramps extending from the street right through the structure, stands just a block away.

Like the Superdome, the Jazz Center would be a piece of urban infrastructure: big, tilting columns raise one end so that street life slips directly underneath the building. Visitors enter by a grand staircase set beneath the bowl of a performance hall. From there, they may continue into a large exhibition space and cafe or climb another staircase to glass-encased foyers suspended above the sidewalk.

The curvaceous walls of the 820-seat performance hall suggest a womb floating within the city’s fabric. A 350-seat “black box†hall sits to one side, separated by a vertical slot of glass — the last glimpse of the outside world before entering the shared intimacy of the halls.

The design reflects longstanding themes in Mr. Mayne’s work. Like many architects of his generation, raised in the postwar optimism that made large-scale civic projects seem possible, he sees the post-industrial city as a work in progress; for him, private buildings, public space and urban infrastructure form a fluid, seamless whole.

Mr. Mayne, more than most, imbues his designs with the progressive postwar social values. His goal is to build better, more refined machines — an especially resonant metaphor in a city suffering because of its neglected, aging infrastructure.

The same impulse infuses the design of Mr. Mayne’s park. On a three-block-long site across Poydras Street from the Jazz Center, the park would require the demolition of the current City Hall, an undistinguished 1950s structure with minor flood damage. A new city hall would rise in its place, flanked by a new state office building and district court house. The existing public library designed in 1959 by Curtis & Davis, the city’s pre-eminent Modernist firm, stands at the park’s northern edge.

This project, an effort to jumpstart downtown development, is still in its nascent stages. Conceived by Strategic Hotels and Resorts (which owns the neighboring Hyatt Hotel), it has yet to receive serious attention from the three levels of government that would pay for most of the construction.

Yet it is possible to discern the architect’s intent. The park is anchored by a great lawn at one end and by a more formal landscape at the other. A series of small band shells, for informal outdoor performances, are embedded in an undulating landscape that frames the park’s outer edge. The band shells are covered by inflatable roofs that help tie the composition together while adding a sense of intimacy.

The results are strikingly different from the unimaginative mix of tourist-friendly casinos, convention centers, retail malls and sports complexes — often with faux historical themes — that transform many urban centers into soulless adult theme parks. Mr. Mayne’s design is based on the classical notion of the city as a vibrant democratic forum: gathering places for a vibrant intellectual and social mix.

The same democratic spirit imbues the waterfront proposal. The stretch of riverfront property near downtown received minimal damage during the storm. But since the 1980s, much of it has been cut off from the city by a warren of ersatz piazzas, retail malls, chain restaurants and a sprawling convention center.

Commissioned by Sean Cummings, a local developer, the plan would give back some dignity to the downtown riverfront. A series of terraces and parks reconnect the city with the waterfront. The cheesy food kiosks at the foot of Canal Street, for example, would be swept away to create a vast plaza stepping down to the water. A reconfigured ferry terminal would bend down to meet the water’s edge.

Farther downstream, the architects propose a vast public park at the end of Poland Street, a main thoroughfare, and a public amphitheater overlooking the water. At the park’s other end, a series of glittering towers would act as a counterpoint to the downtown skyline, visually connecting the eastern and western parts of the city.

In some respects the riverfront proposal reflects the willingness to turn over large segments of the public domain to private interests. The “towers in the park†could be seen as reinforcing class stratification: an enclave of luxurious glass towers overlooking the poverty-stricken neighborhood of the Lower Ninth Ward. Yet the notion of the riverfront as a cohesive element in a fractured city is powerful, especially because it avoids the banal historicism threatening to engulf what’s left of the authentic city.

The problem all three projects face is that they are dependent upon government and private interests mobilizing for the public good. So far, those in charge of the rebuilding efforts have been practicing a form of benign neglect. These new architectural visions will not become reality if business interests are left to rebuild the tourist city while the public realm is ignored.

--------------------------------------------

An architectural model showing a cross section of what the inside and outside of the Jazz Center in New Orleans, proposed by Morphosis.

An artist's rendering of the proposed Jazz Amphitheater.

An artist's rendering of the Bywater Point, proposed by TEN Arquitectos.

An artist's rendering of the Portage Plaza.

An aerial view of the Portage Plaza.

The Riversphere.

The Spanish Plaza.

A rendering of Press Street Landing.

Two Infusions of Vision to Bolster New Orleans

by NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

August 28, 2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/28/arts/design/28jazz.html

In the two years since Hurricane Katrina, what has the rebuilding effort produced? No grand designs. No inspired vision for the future of New Orleans. There have been only a handful of earnest, grass-roots proposals to preserve what’s left of the historic fabric.

Amid this atmosphere of malaise, two recently announced projects for downtown New Orleans stand out as the first truly creative attempts to foster the city’s resurrection. The first, an extravagant proposal for a new New Orleans National Jazz Center and park by Morphosis, is the most significant work of architecture proposed in the city since the Superdome. The second, a six-mile-long park and mixed-use development along the Mississippi, designed by TEN Arquitectos, Hargreaves Associates and Chan Krieger Sieniewicz, would undo decades of misguided building on the riverfront.

The design of the riverfront project has yet to be finished; even the developer concedes that it would take years to build under the best conditions. And construction of the park would probably require the cooperation of city, state and federal agencies — an almost laughable notion, based on recent experience.

Still, the scope and creative ambition of these projects suggest how architecture could someday be vital to the city’s physical and social healing. Both seek to transform dead urban areas into lively public forums, employing powerful architectural expressions of a democratic ideal.

The proposed Jazz Center, designed by Thom Mayne of Morphosis in Santa Monica, Calif., is conceived as a great social mixing chamber, with music embedded in its core. For architects, its form may bring to mind early-1960s “Walking Cities†fantasies by the British firm Archigram: gigantic nomadic machines that could carry entire urban settlements in their bellies.

The center, however, is firmly rooted in the postwar context of downtown New Orleans. Situated on the corner of Poydras Street and Loyola Avenue, it would be flanked by cool glass towers. An elevated section of Interstate 10 cuts through the city just to the west; the imposing form of the Superdome, its broad crisscrossing ramps extending from the street right through the structure, stands just a block away.

Like the Superdome, the Jazz Center would be a piece of urban infrastructure: big, tilting columns raise one end so that street life slips directly underneath the building. Visitors enter by a grand staircase set beneath the bowl of a performance hall. From there, they may continue into a large exhibition space and cafe or climb another staircase to glass-encased foyers suspended above the sidewalk.

The curvaceous walls of the 820-seat performance hall suggest a womb floating within the city’s fabric. A 350-seat “black box†hall sits to one side, separated by a vertical slot of glass — the last glimpse of the outside world before entering the shared intimacy of the halls.

The design reflects longstanding themes in Mr. Mayne’s work. Like many architects of his generation, raised in the postwar optimism that made large-scale civic projects seem possible, he sees the post-industrial city as a work in progress; for him, private buildings, public space and urban infrastructure form a fluid, seamless whole.

Mr. Mayne, more than most, imbues his designs with the progressive postwar social values. His goal is to build better, more refined machines — an especially resonant metaphor in a city suffering because of its neglected, aging infrastructure.

The same impulse infuses the design of Mr. Mayne’s park. On a three-block-long site across Poydras Street from the Jazz Center, the park would require the demolition of the current City Hall, an undistinguished 1950s structure with minor flood damage. A new city hall would rise in its place, flanked by a new state office building and district court house. The existing public library designed in 1959 by Curtis & Davis, the city’s pre-eminent Modernist firm, stands at the park’s northern edge.

This project, an effort to jumpstart downtown development, is still in its nascent stages. Conceived by Strategic Hotels and Resorts (which owns the neighboring Hyatt Hotel), it has yet to receive serious attention from the three levels of government that would pay for most of the construction.

Yet it is possible to discern the architect’s intent. The park is anchored by a great lawn at one end and by a more formal landscape at the other. A series of small band shells, for informal outdoor performances, are embedded in an undulating landscape that frames the park’s outer edge. The band shells are covered by inflatable roofs that help tie the composition together while adding a sense of intimacy.

The results are strikingly different from the unimaginative mix of tourist-friendly casinos, convention centers, retail malls and sports complexes — often with faux historical themes — that transform many urban centers into soulless adult theme parks. Mr. Mayne’s design is based on the classical notion of the city as a vibrant democratic forum: gathering places for a vibrant intellectual and social mix.

The same democratic spirit imbues the waterfront proposal. The stretch of riverfront property near downtown received minimal damage during the storm. But since the 1980s, much of it has been cut off from the city by a warren of ersatz piazzas, retail malls, chain restaurants and a sprawling convention center.

Commissioned by Sean Cummings, a local developer, the plan would give back some dignity to the downtown riverfront. A series of terraces and parks reconnect the city with the waterfront. The cheesy food kiosks at the foot of Canal Street, for example, would be swept away to create a vast plaza stepping down to the water. A reconfigured ferry terminal would bend down to meet the water’s edge.

Farther downstream, the architects propose a vast public park at the end of Poland Street, a main thoroughfare, and a public amphitheater overlooking the water. At the park’s other end, a series of glittering towers would act as a counterpoint to the downtown skyline, visually connecting the eastern and western parts of the city.

In some respects the riverfront proposal reflects the willingness to turn over large segments of the public domain to private interests. The “towers in the park†could be seen as reinforcing class stratification: an enclave of luxurious glass towers overlooking the poverty-stricken neighborhood of the Lower Ninth Ward. Yet the notion of the riverfront as a cohesive element in a fractured city is powerful, especially because it avoids the banal historicism threatening to engulf what’s left of the authentic city.

The problem all three projects face is that they are dependent upon government and private interests mobilizing for the public good. So far, those in charge of the rebuilding efforts have been practicing a form of benign neglect. These new architectural visions will not become reality if business interests are left to rebuild the tourist city while the public realm is ignored.

--------------------------------------------

An architectural model showing a cross section of what the inside and outside of the Jazz Center in New Orleans, proposed by Morphosis.

An artist's rendering of the proposed Jazz Amphitheater.

An artist's rendering of the Bywater Point, proposed by TEN Arquitectos.

An artist's rendering of the Portage Plaza.

An aerial view of the Portage Plaza.

The Riversphere.

The Spanish Plaza.

A rendering of Press Street Landing.